STUDIO

Construction contracts made simple

a team’s journey to fix a broken system

submitted by Marco Mendola

Introduction: what is this all about?

Our team of lawyers, designers, and tech experts spent four years trying to solve a problem that costs the UK construction industry millions of pounds: contracts that nobody can understand. Our template solution shows how even the most stubborn industries can change when you put people first.

Back in 2020, Marco Mendola was working as an in-house lawyer in commercial and construction law, focusing on his legal training, when he hit a wall. He was reviewing construction contracts and couldn’t believe how unnecessarily complicated they were. These weren’t simply hard to read, they were actively making construction projects fail.

Think about it like this: imagine trying to build a stadium, but the instruction manual is written in ancient legal language that even lawyers struggle with. That’s what construction teams face every day.

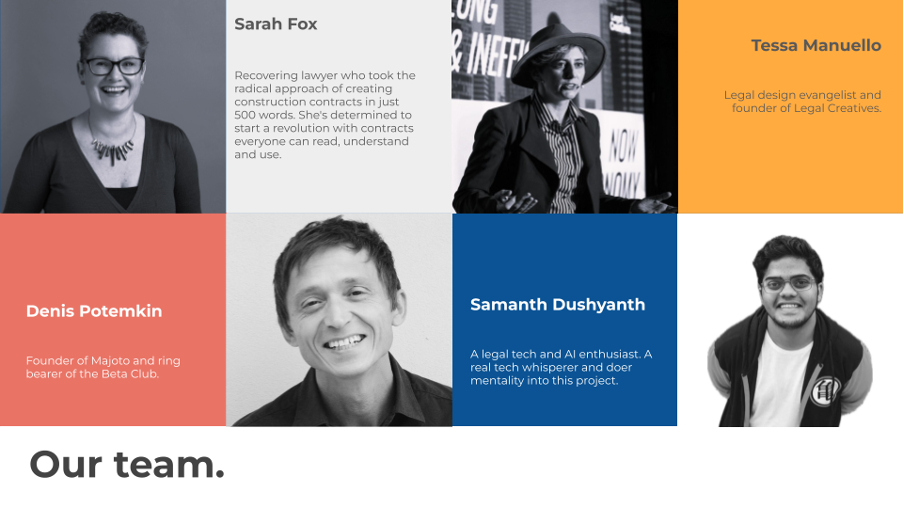

Marco’s experience was so impactful and disillusioning that he spent the following four years investigating this problem. He wasn’t content to just complain about it; he wanted to understand why such contracts had become so broken and what could be done to fix them. Along the way, he found other experts who joined his research journey: Tessa Manuello, Founder of Legal Creatives, who specialises in training legal and contract professionals to make their documents more usable while remaining legally binding; Denis Potemkin, who builds tech & design solutions; and Sarah Fox, leading expert in construction law and practitioner who had already started her mission of writing simpler construction contracts.

Why construction contracts are so broken

Construction law operates like a museum.

Everything stays the same because “that’s how we’ve always done it.” Lawyers copy old contract templates without questioning whether they work for modern projects.

Here’s what this creates in the real world:

Project delays. This happens because teams spend weeks, even months, arguing over contract language instead of building things. Disputes multiply because nobody can agree on what unclear sentences mean. Relationships suffer because contracts are written like battle plans instead of partnership agreements. Good people get frustrated and either avoid construction work or charge more to deal with the headaches.

The human cost is real. Picture an architect trying to figure out if they are legally responsible for something, but the contract explanation runs for thirty pages in legal jargon. Or a contractor who can’t tell when he’ll get paid because the payment terms require a law degree to decode.

Here’s the first page example of a standard T&Cs for Construction & Engineering Works simply to offer a taste of it. Surely, you have seen similar templates so far.

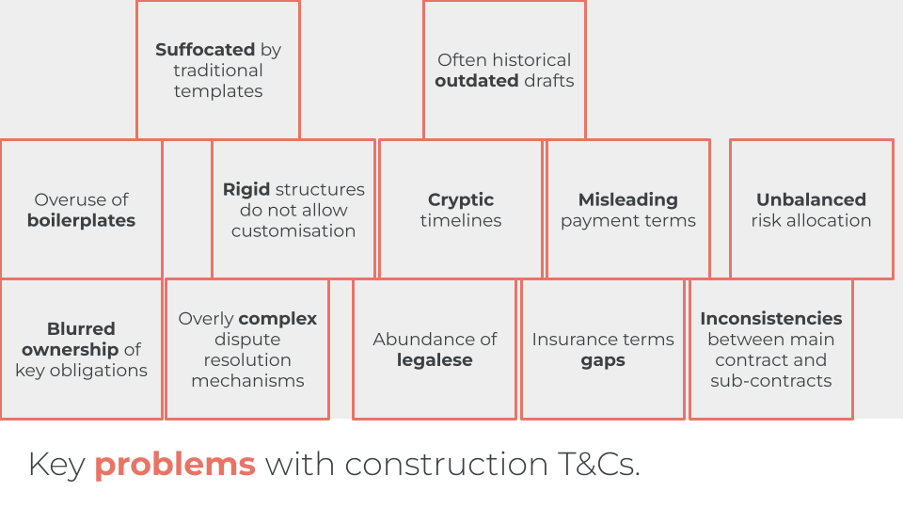

We identified twelve specific ways of how traditional construction contracts hurt projects. Let me group these into three key categories first, and then identify the one by one on a dedicated visual:

Language – The words themselves create confusion. Contracts use archaic legal jargon where plain English would work better. Timelines are buried in complex sentences. Payment terms sound like riddles. When people can’t understand the basic rules, they can’t follow them properly.

Structure – The contracts are built wrong from the ground up. They’re too rigid to adapt to diverse types of projects. Main contracts don’t match their sub-contracts, creating contradictions. Most of the language is just copied from old templates without thinking about whether it fits the actual work being done since 1990 (if, you are lucky).

Process – The way conflicts get resolved is overly complex and expensive. Risk gets assigned in ways that don’t make business sense for anyone. Legal, commercial, and operations workflows often take different pathways, despite referring to the same contracts and relationship. Nobody knows who’s responsible for key decisions. Outdated contract versions keep getting reused because change feels too risky.

The innovation question

We focused our work around one central question: “How might we transform construction law T&Cs to promote collaboration and clarity while breaking free from entrenched traditional terms and practices?”

This question recognises something important: fixing this problem requires both better tools and changing how an entire industry thinks about contracts.

We don’t pretend to fix it all at once but going through this research journey together to show what can be achieved with at least one practical example focused on T&Cs, daring to push some boundaries in an overly traditional and dysfunctional legal sector.

Instead of starting with legal precedents like traditional construction lawyers do, we flipped the script entirely. We began by studying actual construction professionals at work, watching how they struggled with contracts, and asking a fundamental question: what do these people need from a contract to do their jobs well?

Think of it like this: most legal teams approach contract writing like they’re writing for other lawyers. After an in-depth analysis of the user personas involved, we decided to approach it like we were writing a comprehensive user manual for construction workers who need to get things built.

Our methodology followed a systematic three-step approach that you can apply to other complex problems.

Phase One: Debiasing through user immersion (Months 1-6)

The most critical aspect of our methodology was recognising and actively countering the inherent biases that legal professionals bring to contract design. Traditional legal training teaches lawyers to prioritise risk mitigation and precedent-following, which often conflicts with user-centred design principles.

We established a “beginner’s mind” protocol where team members were required to document their assumptions about what construction professionals needed before conducting any user research. These documented assumptions were then systematically challenged through direct user contact.

As a result, we conducted seven one-to-one user feedback interviews (conducted both in writing and via MS Teams) with specialised construction lawyers, civil engineers, and digital services providers. Our interview approach was carefully structured to avoid leading questions that would confirm our pre-existing beliefs.

Let’s share a few examples. Wrong way to ask: “Do you find traditional contracts too complex?” Right way to ask: “Walk me through the last time you had to reference a contract during a project. What happened?”

Our key question types included also:

- “Describe the last time you needed to check payment terms during a project”

- “Show me how you currently find liability information in your contracts”

- “What happens when someone on your team disagrees about what the contract says?”

- “What part of contract review takes the most time in your typical project?”

This phase was followed by systematic peer-review sessions focused purely on plain language simplification, ensuring that our legal expertise enhanced rather than overwhelmed user insights.

Phase Two: Business-first information architecture (Months 7-12)

Traditional legal documents follow a lawyer’s logic: terms and conditions, definitions, liability, termination. Construction professionals think differently: What am I building? When do I get paid? What happens if something goes wrong? Who do I call?

We conducted one comprehensive focus group exercise with representatives from construction engineering firms and contracts experts, facilitated by Sarah Fox. This session used mostly journey mapping to understand how different user types prioritised contract information.

Information architecture principles developed:

- Commercial information first: Payment terms, project scope, and timelines appear before legal definitions

- Progressive disclosure: Complex legal concepts are introduced only after establishing practical context

- Task-oriented grouping: Information is grouped by what users need to do, not by legal category

- Visual hierarchy: Most important information gets most visual weight, regardless of legal precedence

Phase Three: Incremental development with expert validation (Months 13-24)

Rather than developing the contract in isolation, we established a formal mentorship and review process that brought in external expertise at each development stage.

Sarah Fox, creator of the ‘500 Words’ contract series, served as our primary subject matter expert. Her role was to ensure that our simplification efforts didn’t compromise legal effectiveness. We established periodical review sessions where Sarah would assess our latest iterations against real construction scenarios from her practice.

We used Notion as our primary legal design technology tool, which provided several methodological advantages such as template modularity, visual prototyping, and faster turnaround with user testing integration. This technological approach offered new perspectives on contract structure by forcing us to think in terms of modular, interconnected components rather than linear legal documents. Here more details category by category:

- Modular thinking: Rather than writing a contract from beginning to end, we could design individual contract “components” (payment sections, liability frameworks, termination procedures) and test how they worked together.

- Visual-first approach: The platform’s visual capabilities forced us to consider how information hierarchy and layout affected user comprehension, leading to innovations like timeline integration and visual payment schedules.

- Collaborative iteration: Real-time collaboration features meant that legal, design, and technical perspectives could be integrated simultaneously rather than sequentially.

Wrap-up: Collaborative testing and iteration (Months 25-36)

We established an internal research group during the ideation phase, led by Marco Mendola and Denis Potemkin, supported by Sarah Fox and Tessa Manuello. This group combined expertise from the Majoto Beta Club with additional insights extracted from Fox’s ‘500 Words’ contract series.

Each iteration was assessed using three distinct requirements:

- Clarity: Could construction professionals understand their obligations without legal interpretation?

- Completeness: Did the simplified language maintain legal protection equivalent to traditional contracts?

- Collaboration: Did the contract language promote partnership or create adversarial dynamics?

- Give people agency over their legal interests: Our tool is not an opaque algorithm that asks a few questions, then tells what to do. We empower lay people (and experts alike) to understand how legal conflicts can be resolved and that they need to prioritise their goals. This requires a certain level of engagement, but ultimately improves access to justice better than magic turnkey solutions.

- Take the “legalese” out of the “legal”: As much of the authoring is inevitably done by legal experts, we aim to always review our content through the eyes of a lay person. We explain legal jargon, avoid references and concepts that non-lawyers would not understand, and generally try to get rid of legal language wherever it is not absolutely necessary.

- Don’t oversimplify; stay transparent: We aim for “quality simple”: while we strive to make the tool and its use straightforward, we do not hide the complexity of the subject. Whenever our system applies filters or makes recommendations, we inform the user and provide means to understand the reasoning and to modify these variables.

- Be playful while remaining trustworthy: Legal tools don’t have to be dead serious. We try to inject some lightness, even gamification elements, while ensuring that they remain trustworthy and reliable. Decades of UI and usability research remind us that legal design does not have to look like an Excel spreadsheet or a court letter.

- Put user value before “lawyer habits”: Anti-patterns, such as asking users to accept a disclaimer before they even start, are lawyer-centric, not user-centric design. We don’t scare users away with restrictions before presenting results. Better still, we let the content itself convey its limitations. We want to make “legal” approachable, not intimidating.

- Collect as little data as possible: No one dealing with a legal issue wants to be profiled by unknown third parties. We ensure that our front-end never connects to other servers and that no user is tracked in an identifiable way. For our research, we collect minimal usage data in such a non-intrusive way that we don’t even need the dreaded “cookie banner” – that’s great UX, too!

- Keep it accessible and “mobile first”: Removing technical barriers is essential to lowering the threshold for the access to justice. Accessibility is part of the process early on (the “V” in MVP stands for “viable”; excluding users based on ability or equipment is the opposite of viable). We apply the “mobile first” dogma from web design to legal design; always designing with outdated, low-cost smartphones in sub-optimal conditions in mind.

- Simplify the tech stack: Over-engineering is futile. By keeping it simple, we ensure good performance, accessibility and universal usability. “Progressive enhancement” ensures that our application will even work on an old device with an outdated browser, aggressive privacy settings, and slow internet. Radical simplicity also makes maintenance a lot easier.

While succeeding in applying some of these better than others, the emergence of this set of guidelines is in itself an important outcome of our research. This project specifically aimed to identify solution spaces – and room for development and debate – where legal design and interaction design in combination can make law more accessible. The use of interactive media for legal guidance has a lot of potential, but it is also very easy for oversights in design and execution to become a hindrance to aspirational goals.

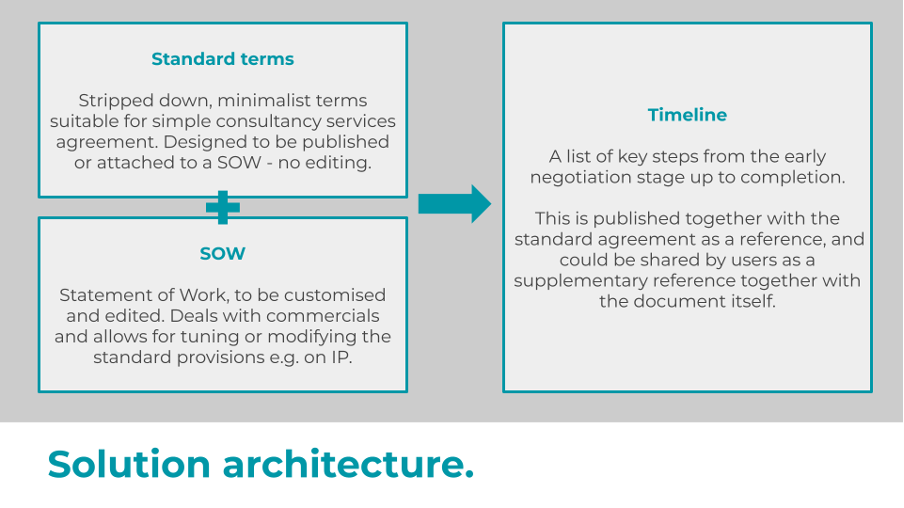

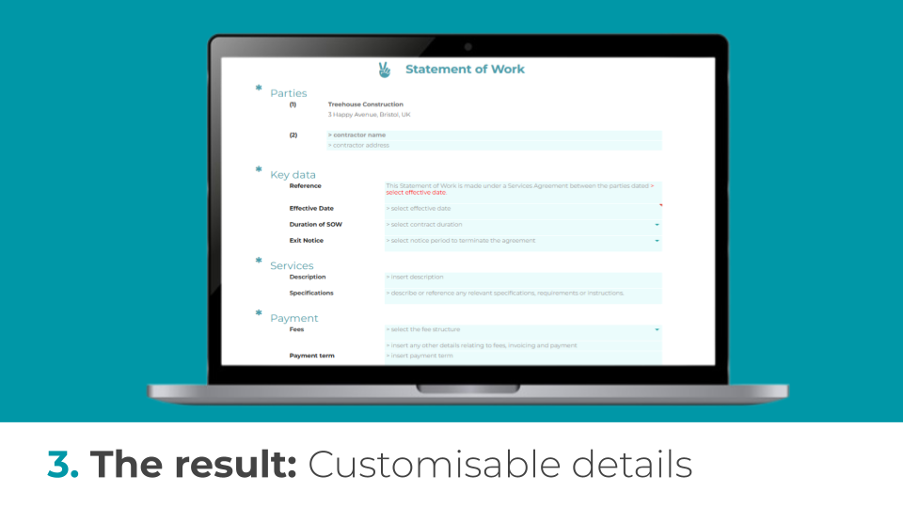

Our three-part template solution

As a result of the above problem identification and research, the diagram below illustrates how we came up to our three-part template solution with a short supporting description:

Making it real

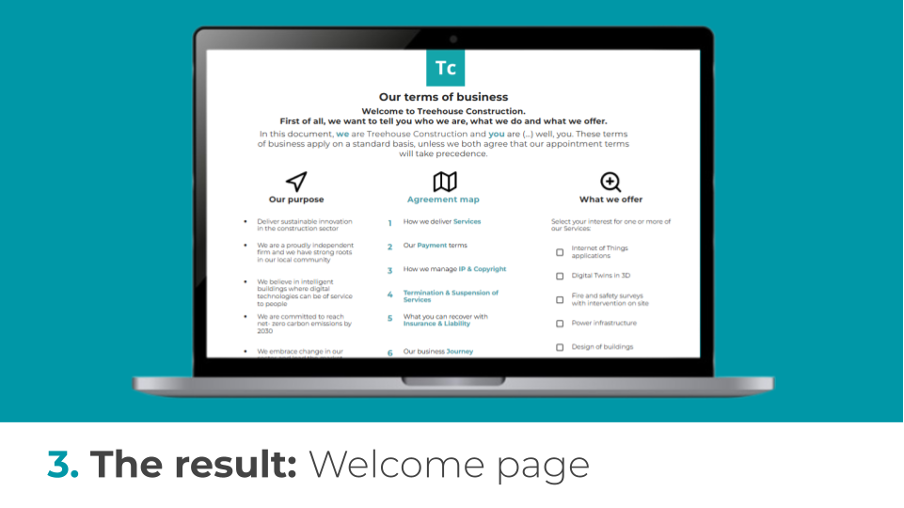

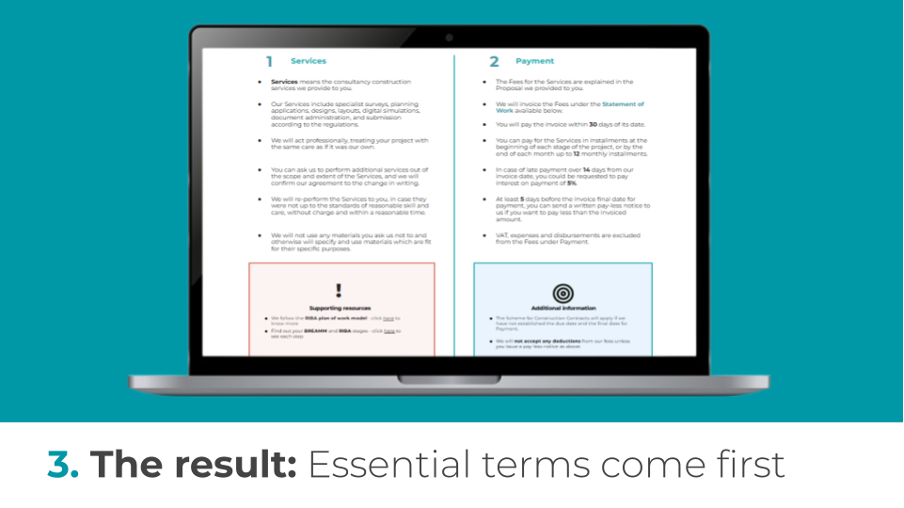

We designed a solution to fundamentally change how people experience construction contracts:

Clear starting point – The contract begins with a welcome page that immediately signals this isn’t going to be another legal maze. People know from the first moment that this document is designed for them to understand.

Important information first – Critical information appears upfront instead of being buried in legal fine print. People can find key commercial terms without hunting through dense text.

Plain language throughout – Complex legal concepts are expressed in clear, actionable language that construction professionals can understand and act on. No translation required.

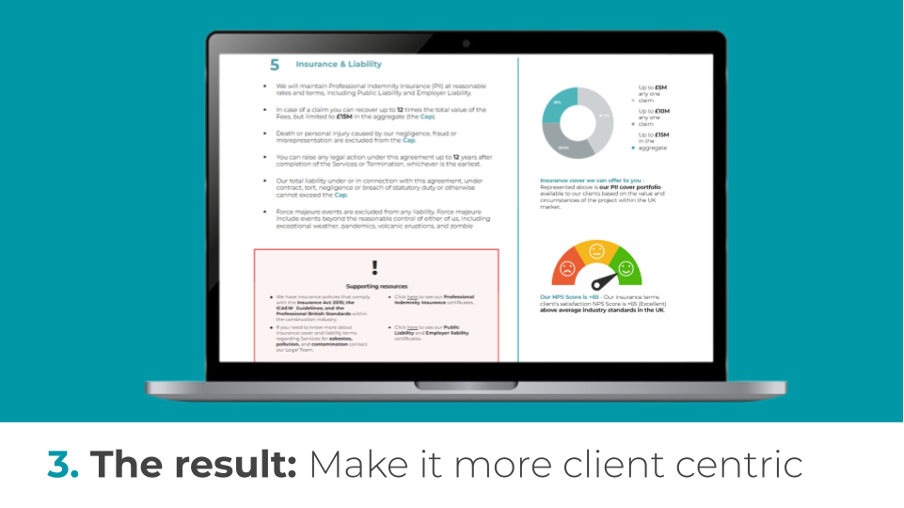

Client-focused structure – The contract organisation follows how clients think about projects, not how legal departments organise files, including clearer data and charts with enhanced data visualisation.

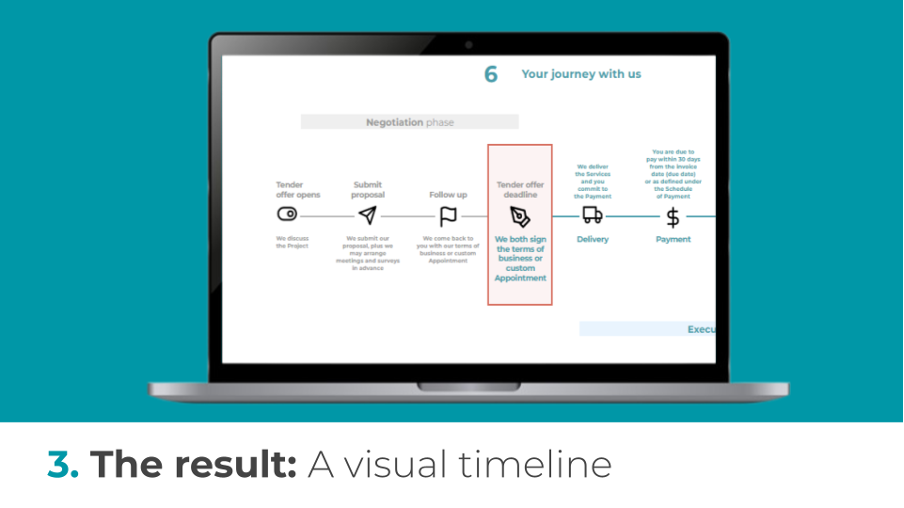

Visual timeline integration – Project progression becomes transparent through visual representation, reducing the misunderstandings that often arise around deliverables and deadlines. Everything in one page, without multiple reminders to different document sections.

Transparent signing process – The last step eliminates hidden terms and surprise clauses, building trust through complete transparency.

Flexibility by design – We understand every relationship is special, and there is not one template able to fix it all. That’s why we have included a simple, clear, and straightforward Statement of Work at the end of the proposed template to check and balance our stakeholders needs.

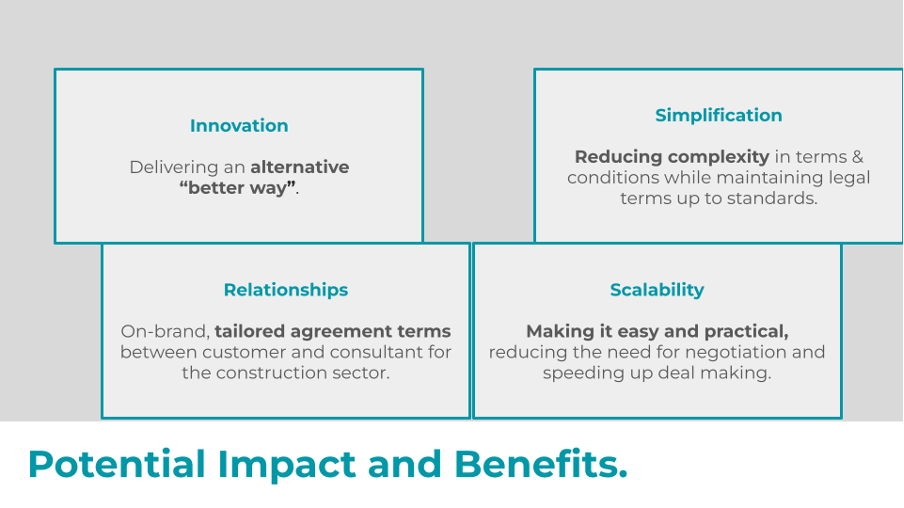

Our T&Cs template aim to produce specific, measurable improvements that you can see in action. These aren’t abstract benefits but real changes that might affect how construction projects get completed and how much they cost. We understand this does not represent a silver bullet for any possible scenario in construction, but – starting from somewhere – we aim to tackle the most common type of scenario represented by terms and conditions of consultancy services.

Dramatically faster deal-making – Traditional construction contract negotiations typically take months or even years as legal teams argue over complex clauses. The simplified approach wants to reduce this negotiation time to days in most cases.

Measurable relationship improvements – The solution created what we call “on-brand, tailored agreement terms” that strengthen business relationships instead of straining them. When people can understand their agreements clearly, they spend their energy on collaborative problem-solving rather than arguing over contract interpretation. Our template aims to reduce drastically disputes and generate better working relationships between contractors and clients.

Significant complexity reduction – We maintained full legal protection whilst dramatically reducing what cognitive scientists call “mental load” (the brain power construction professionals had to spend just understanding their contracts). Where traditional contracts might run 20–30 pages of dense legal text, our solution often accomplished the same legal protection in 5–7 pages of plain language. This meant construction professionals could spend their mental energy on building things rather than decoding legal documents.

Scalability that enables growth – Because the simplified approach eliminates the bottleneck of complex negotiations, companies can take on more projects without proportionally increasing their legal overhead. This scalability benefit helps construction businesses grow more efficiently.

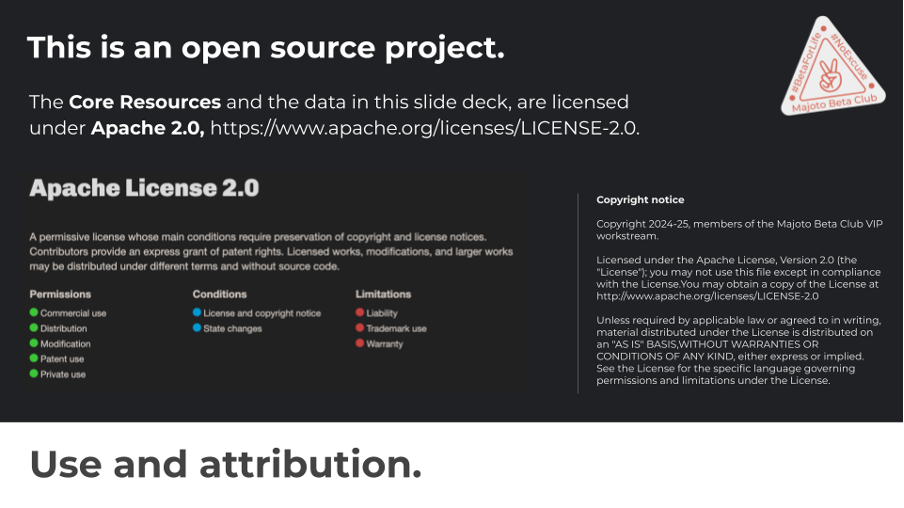

Open-source impact creates industry-wide change – By releasing our template solution under the Apache 2.0 licence, we made a strategic decision that multiplied our impact. This open-source approach means any construction company, law firm, or legal professional can use, modify, and improve our solution without licensing fees or restrictions. The decision transforms our project into a foundation for industry-wide transformation.

Proof of concept for conservative industries – Perhaps most importantly, the project serves as concrete evidence that even the most tradition-bound industries can embrace significant innovation when the human impact is demonstrated, and the solution addresses genuine user needs. This proof of concept creates a template that other legal innovators can adapt for different areas of law that suffer from similar complexity problems.

This project brought together diverse types of expertise developed through four years of collaboration:

Marco Mendola led the project first as Customer Success Lead at Majoto, and then as a Legal Technologist at TLT LLP. He initiated the research during his legal training in-house and brought dedicated study into the construction contract complexity, along with expertise in legal innovation and design thinking.

Tessa Manuello served as the legal design evangelist and founder of Legal Creatives. She supported this use case from its inception and provided mentoring in translating complex legal concepts into user-friendly design solutions that work for busy professionals.

Denis Potemkin founder of Majoto and coordinator of the Majoto Beta Club initiative. He provided the technological framework and innovation platform that made this project possible.

Sarah Fox contributed as a former lawyer who had already pioneered simple construction contracts. She brought proven simplification techniques developed through her independent work in construction law reform.

Samanth Dushyanth joined as a legal tech and AI enthusiast who brought technical implementation skills and responsible to test and iterate the legal tech template.

This collaboration represents what happens when individual expertise across design, technology, and law converges through sustained research and professional relationships built over time.

Thank you

Marco

Download this use case now.

Call for Submissions!

Submit your Legal Design story.

Issue 3

We will soon be receiving submissions for Vol. 3 of the Journal!

Do you want to share your Legal Design Story with the world?

Everyone can submit a use case for review by our expert team.

Here’s how.

How does it work?

We are looking for different kinds of use cases out of different phases of a legal design process.

This part of the Journal will showcase the best work and developments in legal design. This can be in the form of text, digital artifacts, reports, visualisations or any other media that we can distribute in a digital journal format. Text submissions can be between 1,000 and 5,000 words and are reviewed by our Studio editorial team.

What kind of practical use cases can I submit?

Your submission should consist the following:

- Challenge: Describe the problem you had to solve

- Approach: Describe the selected design process and phases you went through in order to solve the challenge. Please insert also a section of the impact that your concept will bring or brought.

- Solution: Show us the solution you developed. Not only with words but with images.

Make sure you do have permission and the rights to share your project an materials (such as images and use case stories etc.)

Why is there a review process?

How does the review process look like and how do we select use cases for publication ?

- Aesthetics

- Depth of concept (Why, What, How)

- Process steps you selected

- Impact

What are the requirements for submission?

Please find a list of requirements and tips here.

Do you want to share your Legal Design Story with the world?

Why publish with us?

Reputation

The editorial teams are comprised of many of the leading legal design academics and practitioners from around the world.

Diamond open access

We are a diamond open-access journal, digital and completely free to readers, authors and their institutions. We charge no processing fees for authors or institutions. The journal uses a Creative Commons BY 4.0 licence.

Rigour and quality

We are using double blind peer review for Articles and editorial review for the Studio. Articles are hosted on Scholastica which is optimised for search and integration with academic indices, Google Scholar etc.

Your Studio Editorial Collective

Do you want to see more use cases ? Take a look at the websites of some of our Studio editorial team.