STUDIO

In this article:

In France, since the introduction of the term videoprotection in the 2011 LOPPSI 2 law, surveillance has become a major topic of public debate. But surveillance today is no longer limited to the watchful eye of public authorities. It now extends into a complex ecosystem that includes private companies and even citizens themselves. Nor does it merely observe: it anticipates, calculates, prevents, and suggests. Often invisible, always diffuse, surveillance seeps into our everyday gestures, our movements, our decisions.

Some narratives portray it as protective, even benevolent. Others claim it helps optimize and streamline our daily experiences. Yet as this quiet omnipresence settles in, a recurring question emerges: what have we agreed to lose in the name of efficiency, safety, or convenience? Where does protection end, and where does control begin? How much arbitrariness hides in algorithmic decisions? What freedoms are we willing to curtail to uphold a presumed order in public space?

These tensions formed the starting point of an original pedagogical project that brought together, from October 2023 to January 2024, law students (LL.M in Intellectual Property, Information Technology & Space Law, Paris-Saclay University) and design students (MDes in Industrial Design, ENSCi–Les Ateliers). Supported by the Pedagogical Innovation Directorate and research labs at Paris-Saclay, these young jurists and designers set out to explore the ambiguous terrain of contemporary surveillance, together.

The project followed a dual ambition: (1) to introduce law students to the speculative, critical, and experiential dimensions of design; (2) and to invite design students to engage with legal thinking, not as a constraint but as a material to be reimagined, diverted, and reshaped. A dialogue in which each discipline, rather than stepping aside, learned to enrich the other.

But what kind of surveillance are we talking about, exactly? The cameras in our streets? The smart meters in our homes? The apps that track, compute, and notify? The platforms that profile our cultural tastes? We are no longer facing one single form of surveillance, but rather a constellation of technologies, logics, and regimes: a plurality of surveillances, whose effects the law attempts to regulate. To do so, it sets limits, principles of proportionality, safeguards. But between the lines of legal texts and judicial decisions, grey areas persist: interstitial spaces where the ambiguous, the possible, and the contestable slip in.

It is precisely in these in-between spaces that the students chose to intervene. Through design fiction, controversy mapping, and mediation devices, they gave tangible form to their questions. Ambiguous objects, fictional interfaces, unsettling yet plausible services: their artifacts, whether frictions or fictions, materialize the undecidable, the uncomfortable, the “too possible.”

In the face of a legal framework that doesn’t always align with what is desirable, one question remains: how can we think and represent the limits of legitimacy in the age of surveillances?

To meet the challenge set before them, students worked over two consecutive phases, each lasting four months.

Controversy Mapping Studio (October 2023 – January 2024)

The first phase took the form of a studio focused on exploring surveillance through mapping. A first group of students was tasked with producing a cartography of contemporary surveillance practices, combining legal and design-driven approaches. To do so, they adapted the methodology of controversy mapping developed by Bruno Latour and his collaborators at SciencesPo, tailoring it to their dual background (law and design) and to their specific subject of inquiry.

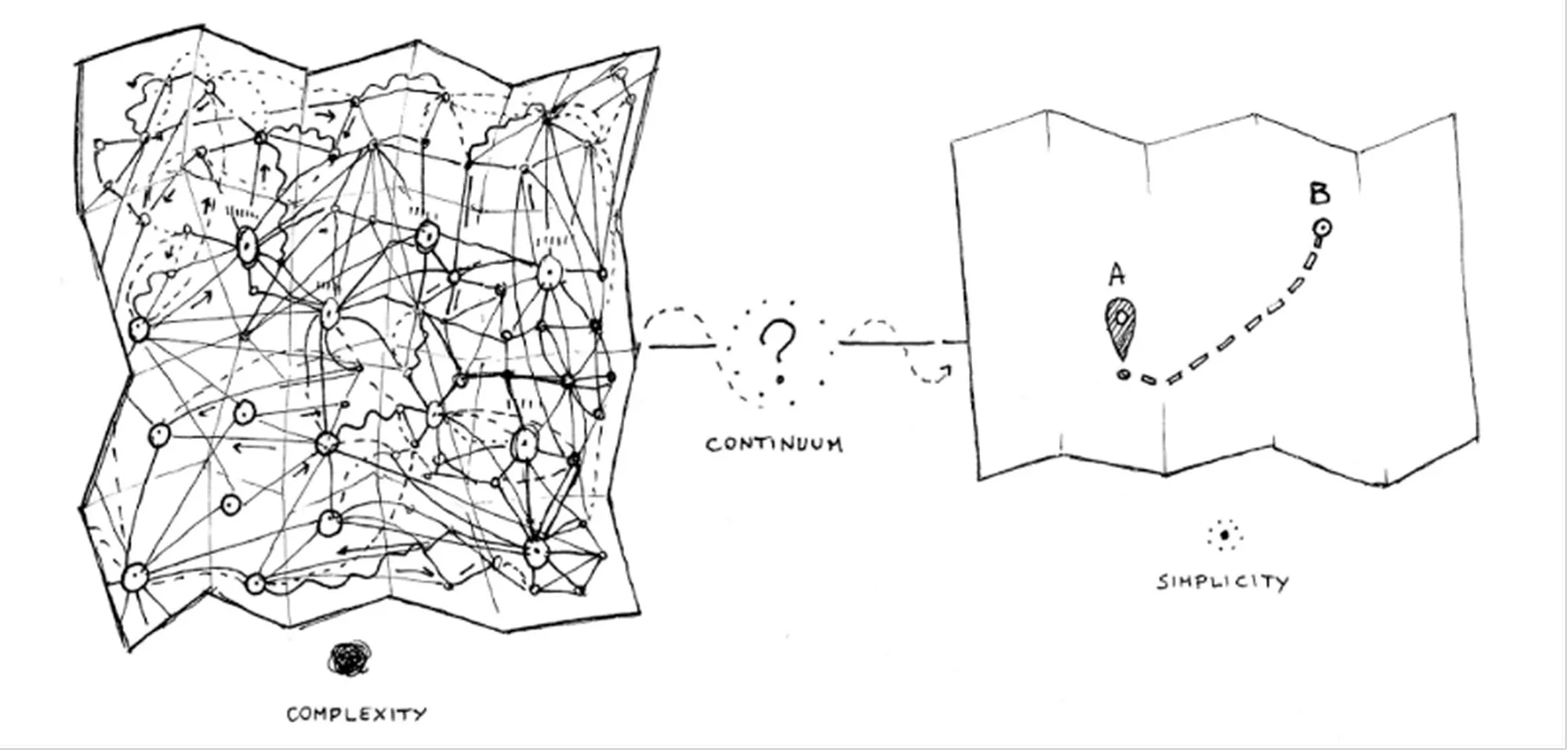

Controversy Mapping (CM) is a teaching and research method that originated within Science and Technology Studies (STS), designed to explore and visualize contemporary sociotechnical issues. Positioned at the intersection of sociology and design, web-mining and fieldwork, CM offers an empirical approach to analyzing issues characterized by conflicts between diverse groups of actors. Its central aim is to produce visual representations that make complex debates accessible and intelligible to a broad audience. Navigating a continuum between simplicity and complexity, the method strives to capture the richness of controversies without creating maps so detailed that they become impractical or obscure.

Two maps both unsatisfactory but for opposite reasons (2015), Daniele Guido

(in T. Venturini & al. Designing Controversies and Their Publics. 31(3) Design Issues 74, 2015, p. 74).

This methodology involves identifying the key actors, stakes, tensions, and narratives that shape and sustain a complex issue, without attempting to resolve or simplify its internal contradictions. Rather than reducing controversy to a binary opposition or a linear storyline, controversy mapping seeks to highlight the multiplicity of perspectives, the evolving alliances and oppositions, and the layered nature of disputes. By tracing how knowledge, values, and interests are mobilized and contested across different forums—scientific, legal, political, economic, and media-related—this approach provides a nuanced and dynamic understanding of how sociotechnical controversies unfold in real time.

Within this framework, students learned to detect and analyze points of friction related to surveillance technologies, ranging from contested uses and value-based disagreements to zones of legal ambiguity and the shifting roles of public and private stakeholders. Through the study of concrete legal cases and extensive documentary research, they mapped the interconnected social, economic, and regulatory landscapes in which these technologies operate. Special emphasis was placed on the visual representation of these tensions, enabling students to articulate the complexity of the issues in a clear, structured, and accessible form.

The studio served a dual purpose: to train students in a structured and critical reading of a complex legal issue, and to document the stakes that would inform the next, more design-oriented phase of the project. The studio was led by Antoine Boilevin (Legal Design Lead, Ubisoft) and Fabien Lechevalier (Legal Scholar, Paris-Saclay University). Students participated one half-day per week.

Example

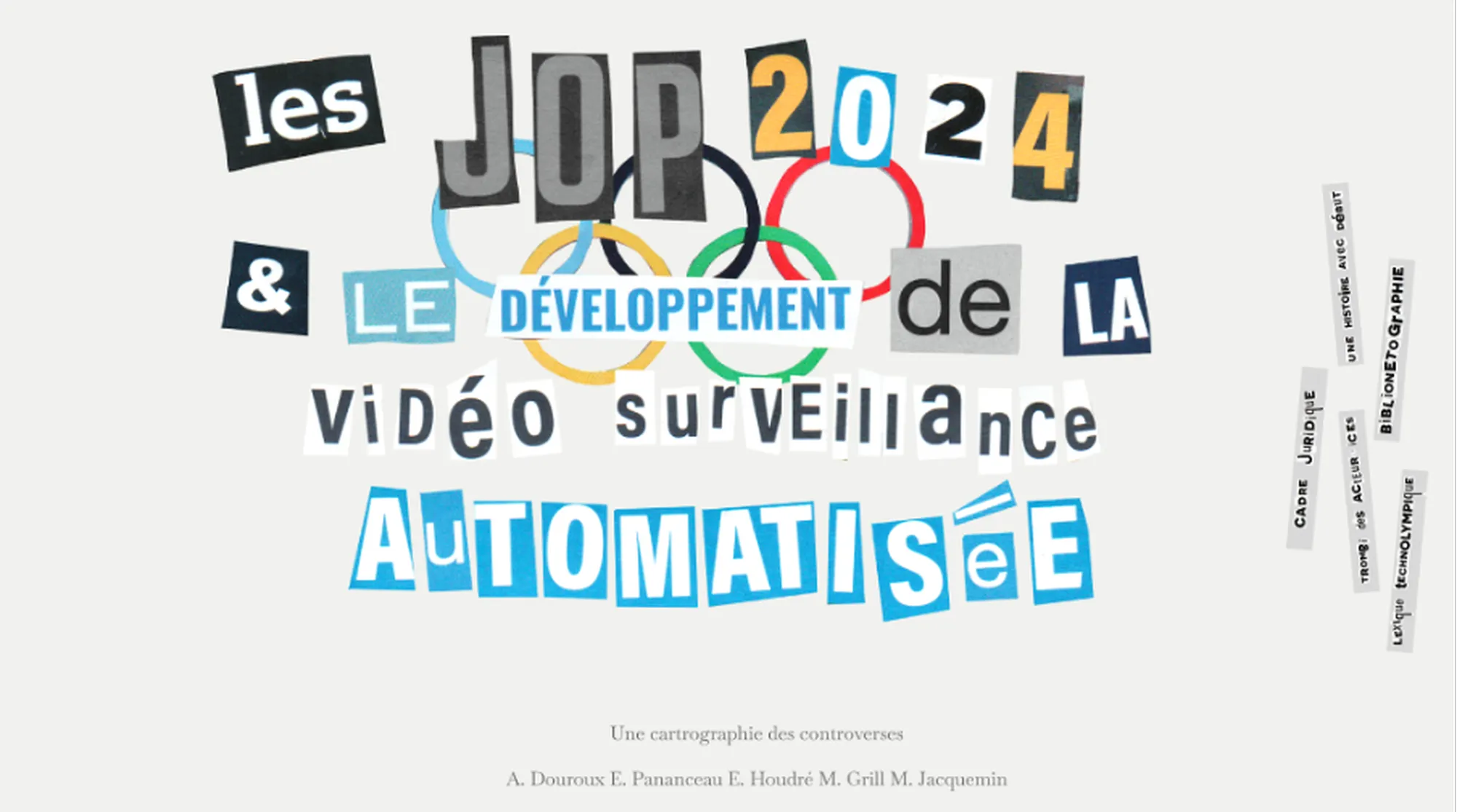

Mapping project by a group of students who investigated the deployment of automated video surveillance under the law of May 19, 2023, related to the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

To discover this controversy map, click here

Designers: E. Pananceau, M. Jacquemin; Lawyers: A. Douroux, E. Houdré

Design Fiction Studio (October 2024 – January 2025)

The second phase of the program took the form of a project-based studio, extending and transforming the research initiated during the CM phase. It was led by Estelle Hary (Design Researcher, RMIT), Lisa Dehove (Independent Designer), and Fabien Lechevalier (Legal Scholar, Paris-Saclay University). Design students participated four half-days per week, while law students contributed one half-day weekly.

Phase 1 – Deepening through inquiry

The cartographic work begun the previous year found continuity in this studio through a complementary methodological angle. Rather than starting from controversies, students began with a specific technical device. Using research methods inspired by ethnography (observation, interviews, ecosystem analysis), they investigated the technical and legal conditions under which these devices operate. Each group produced a printed deliverable, freely designed in form (maps, narratives, diagrams), that synthesized the defining features of the system studied in its real-world environment. Given that the students involved were not the same as those in the previous phase of the project, this short phase also served as an opportunity for the new team to familiarize themselves with and take ownership of the work carried out the year before.

In parallel, instructors provided theoretical input to equip students with tools for inquiry: fieldwork methods, legal basics for designers, and principles of information design for law students.

Example

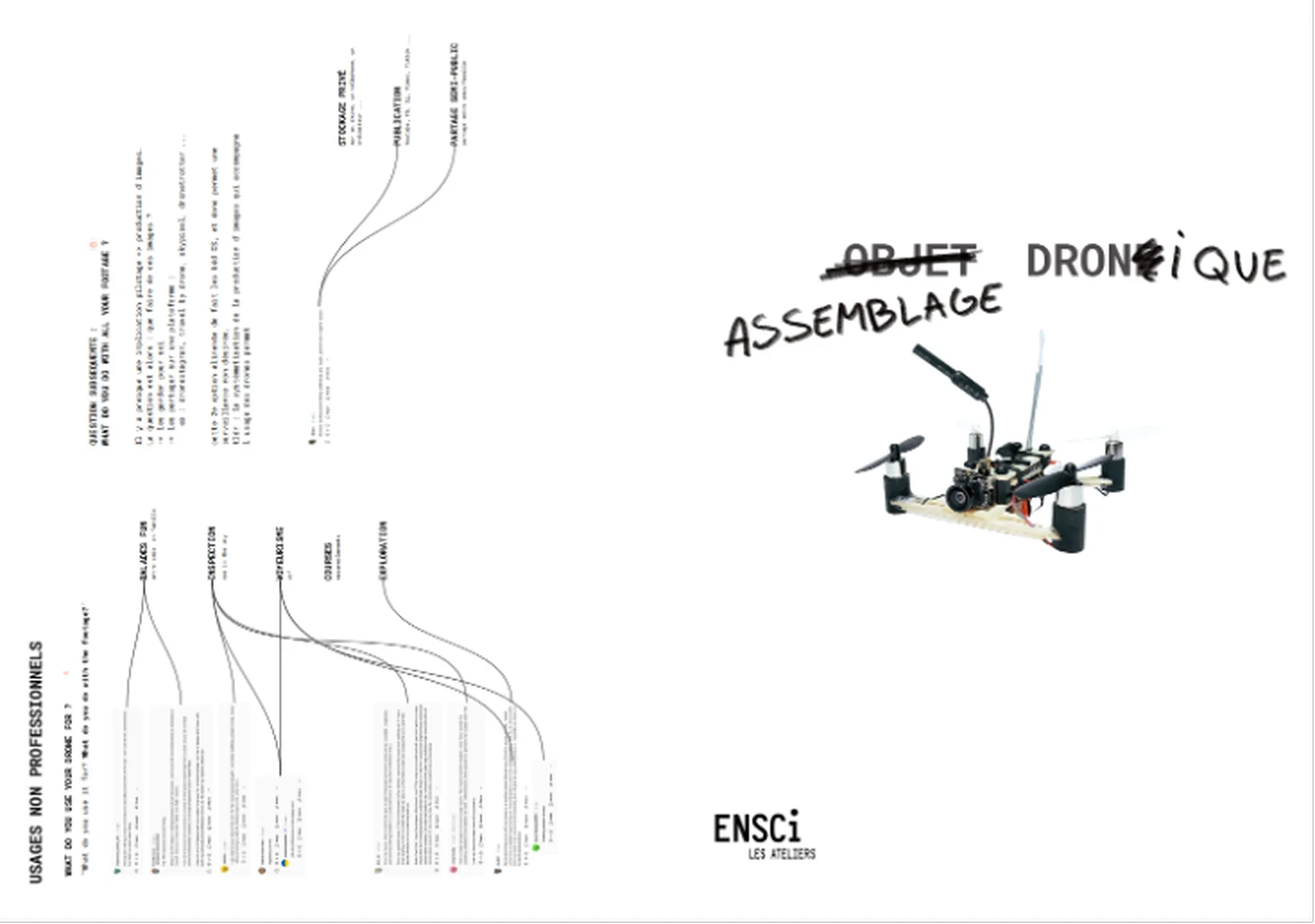

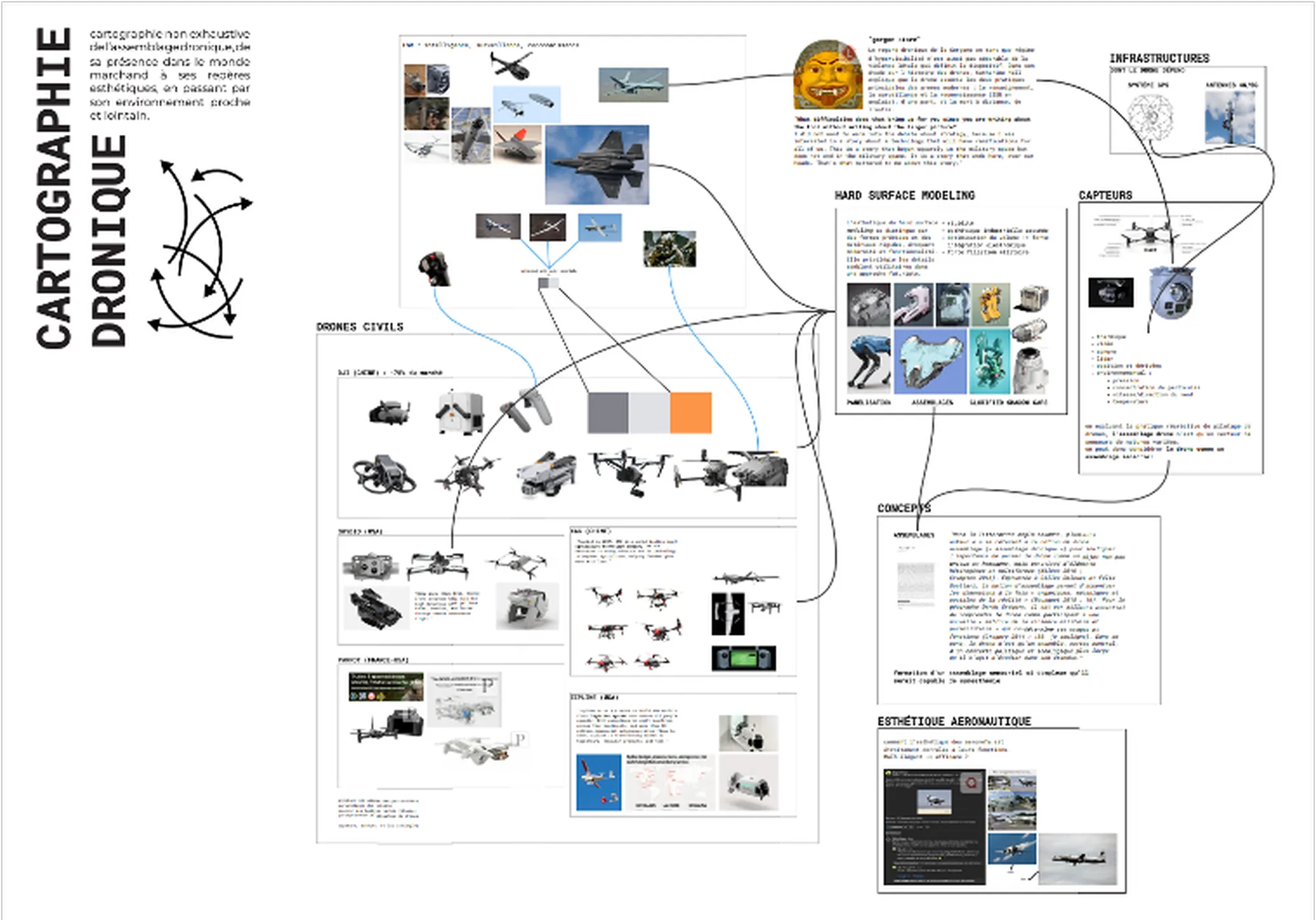

Field inquiry by a group exploring drone-based surveillance.

Designer: A. Gignoux; Lawyers: A. Lahrech, Y. Abdel Moneim

Phase 2 – Rewriting the rules, imagining futures

The second phase created space for critical speculation through the practice of design fiction.

To support this speculative process, students drew on methods from the sociology of imaginaries, a field that examines how collective visions of the future shape contemporary institutions, technological choices, and regulatory frameworks. Building on the work of scholars such as Sheila Jasanoff (sociotechnical imaginaries), Cornelius Castoriadis (social imaginaries), and Pierre Musso (industrial imaginaries), they critically examined the dominant narratives underlying current surveillance regimes (e.g. promises of efficiency, security, and sovereignty) and analyzed how these narratives influence normative frameworks, whether legal, social, or design-related. Using techniques such as scenario building and narrative mapping, students identified competing imaginaries and brought to light the values, fears, and aspirations they carry.

By the end of this process, three distinct types of inquiry had emerged: a mapping of contemporary controversies, an ethnographic study of the technical systems at the heart of those controversies, and an investigation into the imaginaries that inform them.

Thanks to worldbuilding practices drawn from design fiction, students created alternative futures in which the studied technologies were transformed, reinterpreted, or regulated differently. These futures were neither purely utopian nor dystopian, but were structured around coherent internal logics, with their own political balances, economic systems, and cultural norms. The interdisciplinary nature of the exercise, at the intersection of design and law, made it possible to imagine hypothetical legal frameworks tailored to these speculative futures. Law students contributed by drafting fictional legal provisions or designing new institutional architectures. This exercise led to the exploration of speculative legal design: how can a legal rule, court ruling, or technical standard reshape the materiality of an object? What kind of society does an alternative legal framework make possible or impossible? The objective was to construct an immersive world conducive to the emergence of an idea. The next step was to give life and form to a mental image through design concretized as a speculative prototype. In order to do so, students reinjected their hypotheses into their initial object of study, probing how it might evolve under new social or legal conditions, and exploring the legal implications of these changes.

We could summarize the process followed in several key steps:

- Speculative personas: grounding imagined futures in contexts that are both plausible and provocative.

- Use scenario: aligning the overarching vision with the core idea.

- User experience: reflecting on how the solution might be used and experienced.

- Proof of concept: designing deliverables related to the artifact sketched through drawings, storyboards, narrative prototypes and objects intended both to provoke debate and serve as tools for public mediation.

- Tangible prototype: giving concrete form to the concept, bringing fiction closer to reality.

- Narrative development: crafting a compelling storyline to make the concept’s potential credible and accessible.

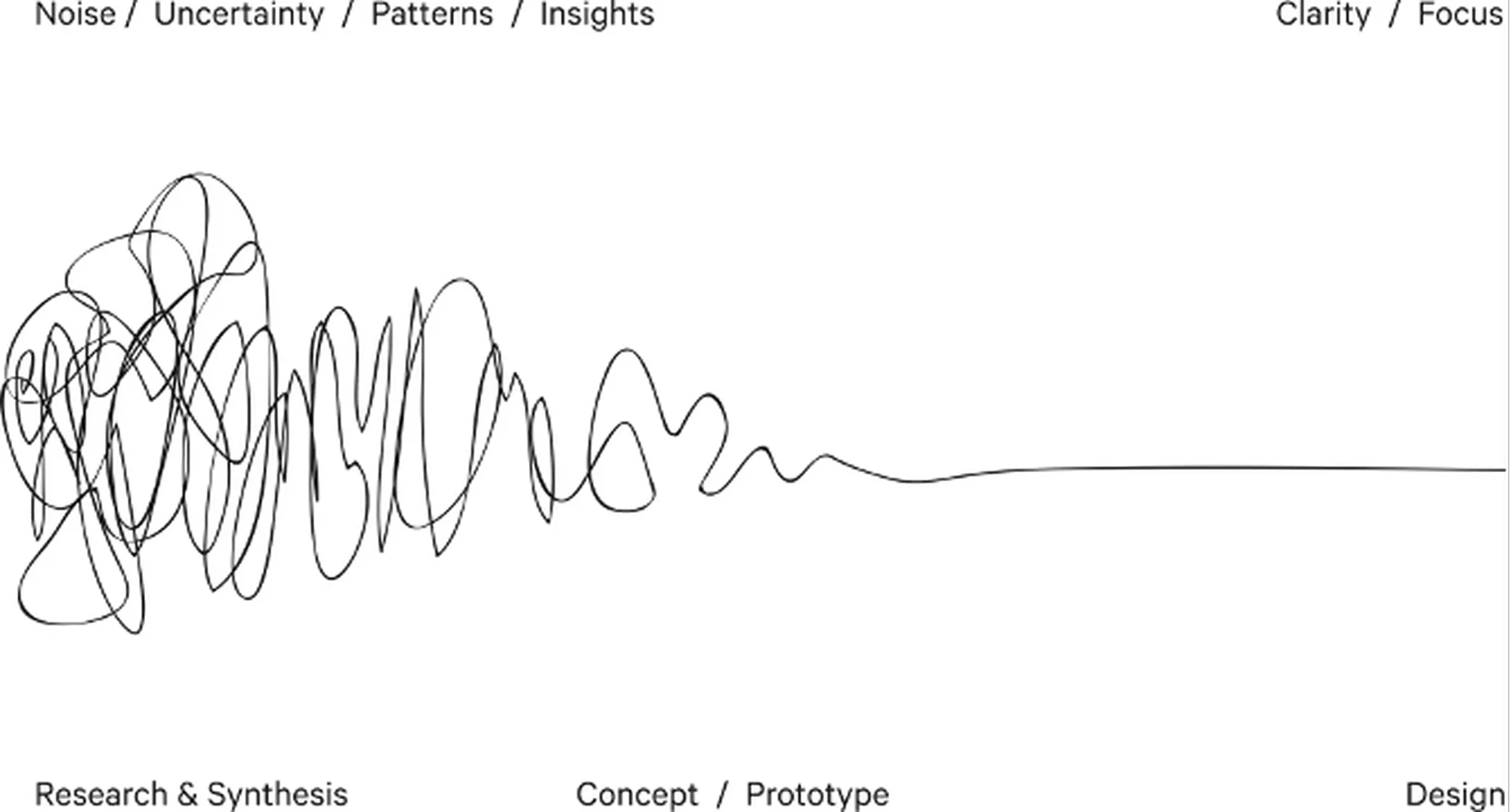

We invite the reader to take a certain distance from the methodological path as it is presented here. Rather than following it as a fixed sequence of steps, we encourage an exploratory and intuitive engagement: to move back and forth, to revisit phases, and to respond to what emerges in relation to the material, the context, and one’s own sensibility (see The Process of Design Squiggle). Design, after all, is not a standardized method but a discipline rooted in perception, intuition, and iteration. It calls for attentiveness rather than prescription and unfolds as a dialogue with the environments, constraints, and imaginaries it engages with.

The Process of Design Squiggle (2002), Damien Newman

Drawing on their research and scenario work, the students designed a series of design fiction artefacts as tools for public discussion. These speculative prototypes serve as entry points into the questions each group chose to raise. The artefacts vary in nature: technical objects, services, human–machine interfaces, and even fictional legal forms such as laws, court rulings, legal opinions, or calls for tender. All were conceived as tools for mediation, material narratives of possible futures.

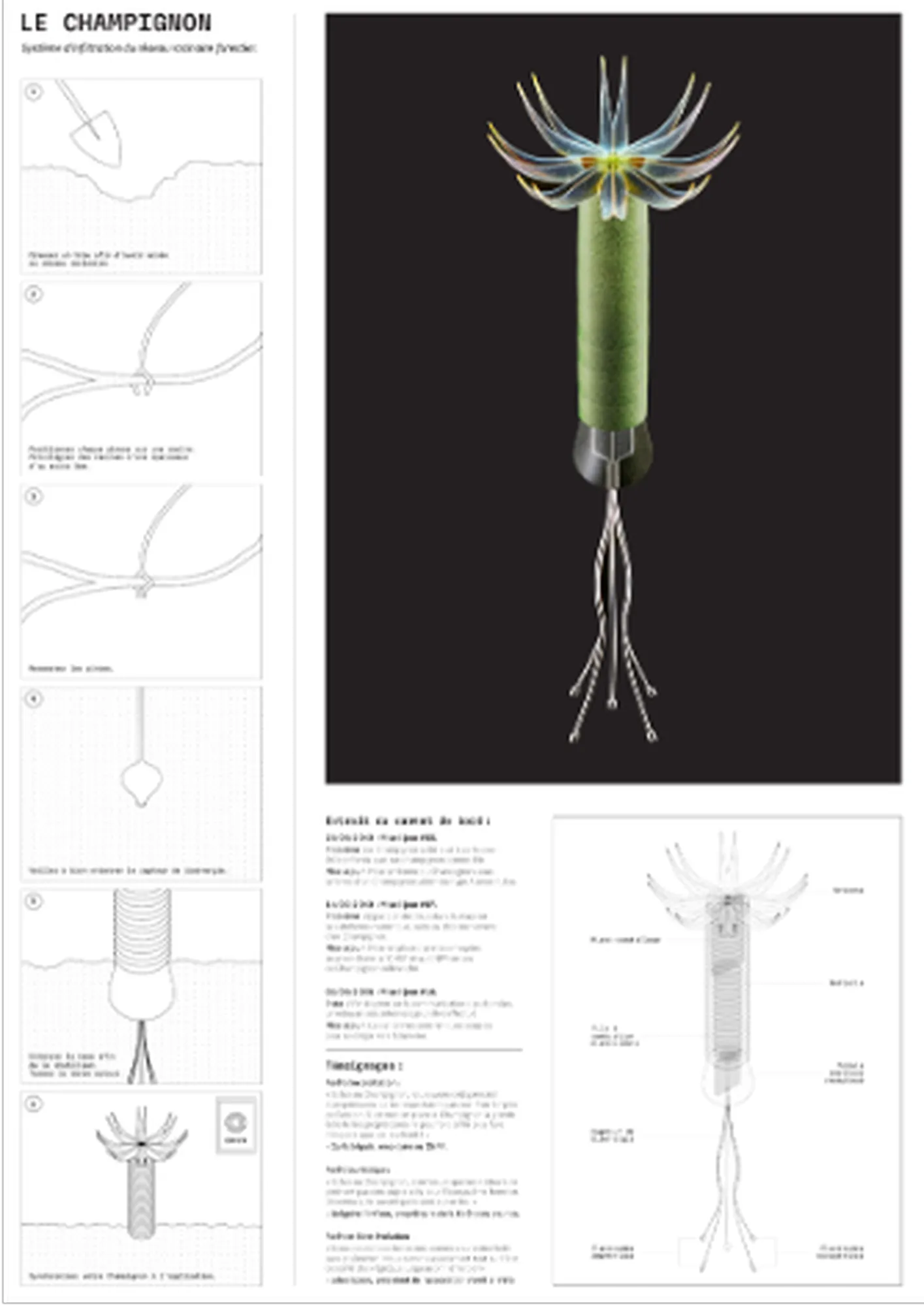

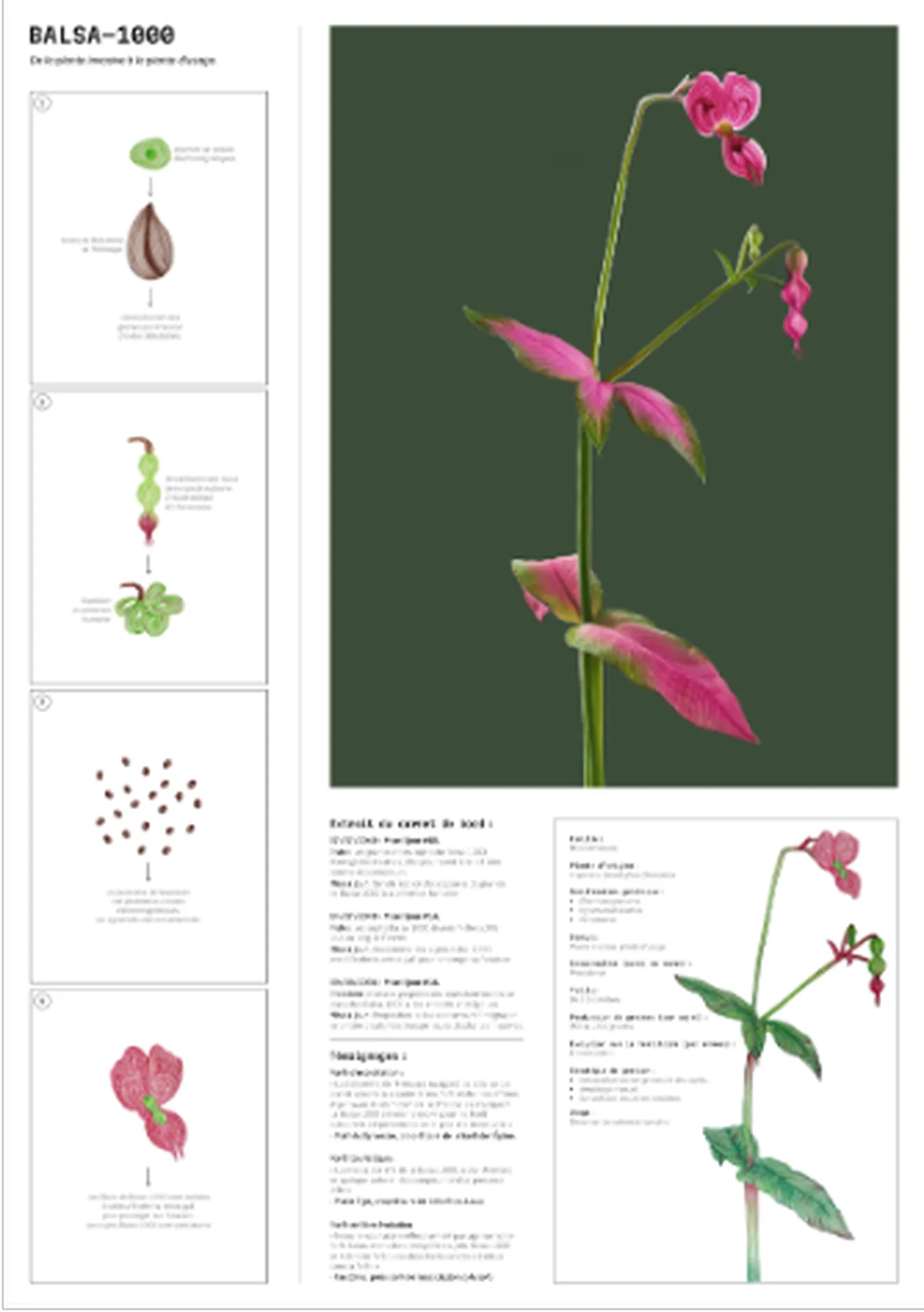

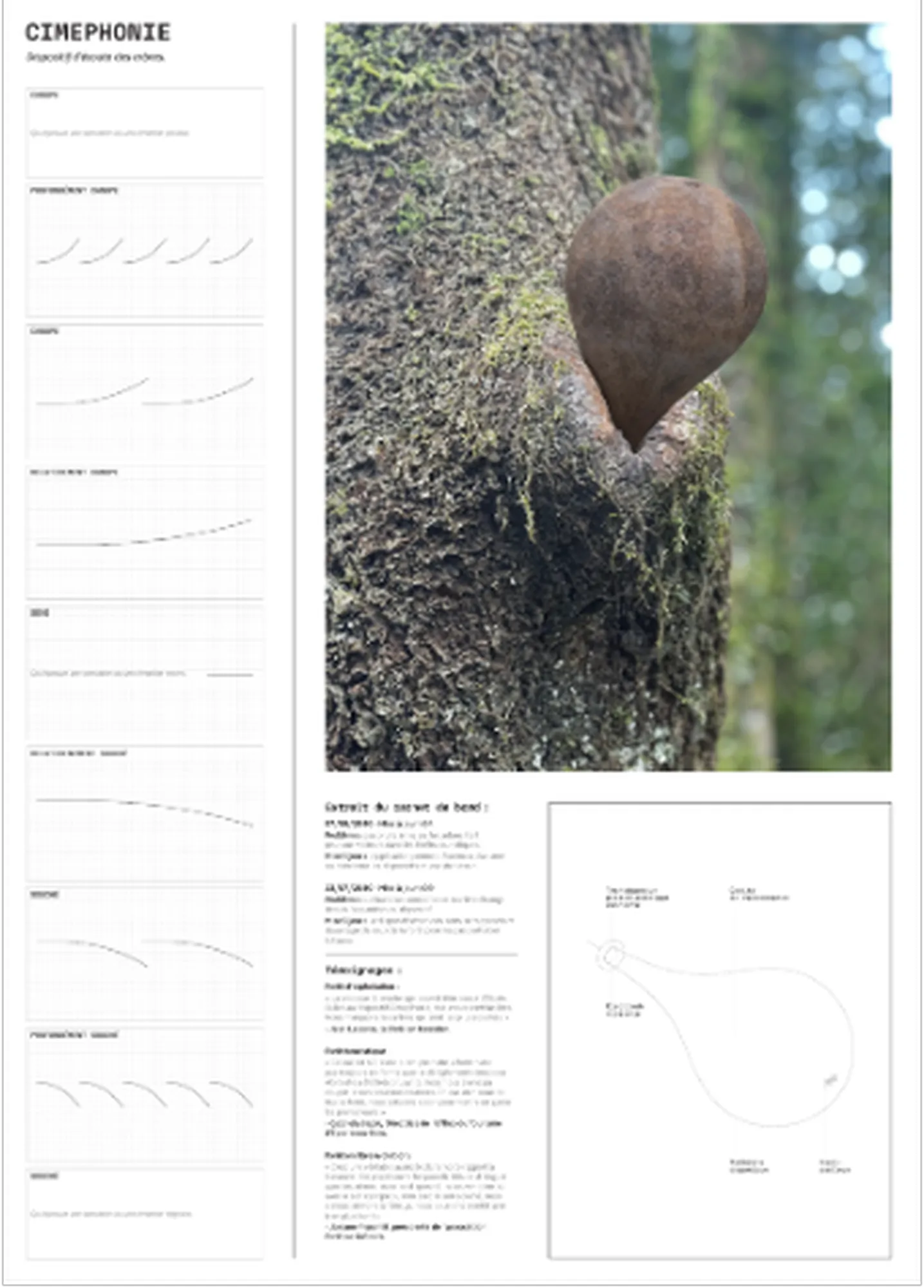

Sample artefact — Surveillance for the Common Good

Project: Public Call for Tender – Centralized Forest Management in France

One group focused on the issue of environmental surveillance, with a particular emphasis on forests. Their fiction unfolds in the year 2034, when the Ministry of Ecological Transition and Biodiversity issues a national call for tenders, inviting research laboratories to propose a new forest monitoring system.

In this scenario, you play the role of the jury tasked with selecting one of three finalist systems—each based on a distinct technology, and each raising specific legal concerns. One proposal, for instance, titled Ciméphonie, suggests an audio monitoring system that quite literally gives trees a voice. By anthropomorphizing plant life, the project explores the growing legal discourse around granting forests juridical personhood, and interrogates the boundary between symbolic representation and enforceable legal status.

Your choice of technology is not neutral, it determines the system’s future social and legal impacts. Depending on your decision, you are invited to discover the unintended consequences of its implementation through the reading of a fictional court ruling, written by the students.

Designer: L. Petit–D’Heilly; Lawyers: M. Praire, M. Barranco

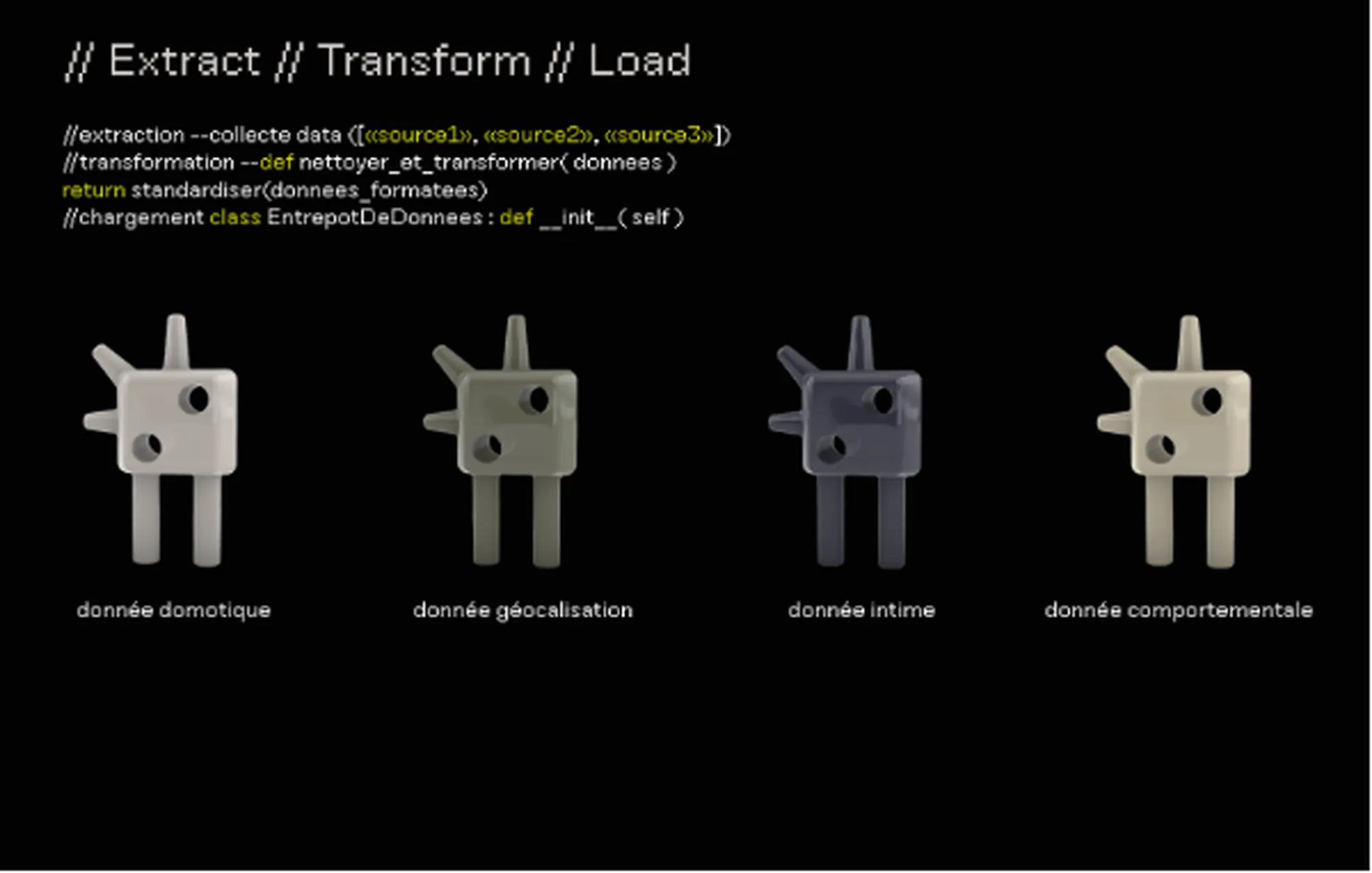

Sample artefact — Dataveillance

Project: Data Lyke

This project questions our relationship to personal data collection and valorization, through an installation where the digital meets the tangible—making visible the often invisible mechanisms of surveillance. At the heart of the installation, an interactive screen presents visitors with a series of dilemmas drawn from a near-future in which data has become the dominant currency.

“Would you accept to share all your home energy consumption data in exchange for a 50% discount on your bill? Would you agree to be geolocated in real time by airlines in return for free flights?”

These are not abstract questions. They ask what you are willing to trade, and for what purpose, or for whom. At the end of the questionnaire, each participant is invited to place a physical module into a collective installation, representing their answers. Identical in shape, the modules vary only by color, with each hue corresponding to a specific data type: intimate, domestic, biometric, geolocation, etc. These objects embody the technical stages through which data passes in AI systems: Extract, Transform, Load—three core operations of algorithmic processing. Here, those abstract steps are rendered visible, even tactile.

Designer: T. Berard; Legal scholar: P. Durance

These projects culminated in a traveling exhibition curated by the Design Spot Paris-Saclay. The first presentation took place at Lumen (Paris-Saclay) from May 10 to June 10, 2025. The exhibition was then hosted by CNIL (French Data Protection Authority) in July, with a further installation planned for January 2026 at ENSCi–Les Ateliers. More than just a showcase, the exhibition serves as an invitation to question established norms—to explore what the law permits or merely tolerates, and to imagine futures where technology serves without subjugating. Beyond its educational scope, the project contributed to raising public awareness of legal design. Through the traveling exhibition, the speculative artefacts became tools for public engagement, offering accessible ways to explore legal questions on surveillance issues. By giving form to abstract legal debates, the project helped make legal design visible and tangible to a broader audience.

However, it is worth recalling that the primary, and perhaps even implicit, ambition of this project was pedagogical: to test, in a concrete setting, the conditions for collaboration between legal and design students, in order to explore what each discipline can contribute to a design project centered on law.

The project demonstrated that truly rigorous and meaningful legal design relies on the complementarity of expertise. The goal was not for law students to become designers, nor for designers to become legal experts, but to recognize that each discipline holds specific and essential skills for the other. A plausible legal design project requires both the legal accuracy and knowledge brought by lawyers and the designers’ ability to visualize, narrate, and prototype.

Throughout the sessions, this collaboration allowed each group to become familiar with the tools and culture of the other. Designers supported law students in exploring methods of visual representation such as mapping or digital prototyping with tools like Figma. In return, law students guided designers in discovering legal reasoning, using legal databases, and analyzing judicial decisions. Each skill was rooted in a real professional practice and transmitted not only vertically by instructors but also horizontally between peers.

This real-life framework also introduced students to a hybrid professional mindset: learning how to collaborate across disciplinary boundaries, recognizing the value of another professional language, and expressing their needs in terms the other can understand. Law students had to learn how to reframe problems through scenarios, case studies, and graphic representations. Designers, on the other hand, were faced with the precision of legal vocabulary, the formal structure of legal texts, and the adaptable nature of legal rules.

To learn more and view the exhibition catalogue click here.

Design about law

Ultimately, the project allowed us to experiment with a pedagogy of interprofessional collaboration in which the dialogue between law and design is not based on vague compromise, but on the mutual recognition of disciplinary expertise as a necessary condition for meaningful and generative co-creation.

From an epistemological standpoint, the project also opened a space for critical reflection on the very foundations of legal design. Too often, legal design is reduced to a set of communication tools or user-centered methods aimed at improving access to law. In this sense, it remains largely confined to a design philosophy derived from design thinking. However, legal design cannot be reduced to design thinking, a model that, strictly speaking, has no solid grounding in the history of design as an academic or professional discipline[1].

In contrast, the speculative approach explored here proposes a more reflective and critical mode of engagement. It no longer seeks simply to optimize legal tools and interfaces, but rather to interrogate the assumptions underlying legal systems, reimagine their architectures, and stimulate debate about the futures of law itself.

This shift from instrumental design to critical and speculative design signals a broader epistemological turn: moving from designing for law to designing about law, and about legal norms as such. It invites legal scholars to consider fiction not merely as a pedagogical device or rhetorical technique, but as a generative method capable of articulating normative questions that legal doctrine alone may struggle to bring into focus. In this sense, speculative legal design offers a powerful framework for rethinking what law is and what it could become.

The pedagogical value of the project thus lies not only in its outputs, but in the transformation of perspectives it enabled: learning to work with disciplinary difference rather than against it, and recognizing speculation as a legitimate mode of inquiry, both in design practice and in legal education.

[1] “Design thinking is not design. Design thinking is to design what the scientific method is to science. It’s the steps without the knowledge and the years of training. And design thinking is a real danger because many companies think they’re doing design and they’re not. So it’s become a real consultant’s playground, and a way for many companies to abdicate their responsibilities towards design.”, “Paola Antonelli interview: ‘Design has been misconstrued as decoration’” (2013), The Conversation. Online.

Download this use case now.

Call for Submissions!

Submit your Legal Design story.

Issue 3

We will soon be receiving submissions for Vol. 3 of the Journal!

Do you want to share your Legal Design Story with the world?

Everyone can submit a use case for review by our expert team.

Here’s how.

How does it work?

We are looking for different kinds of use cases out of different phases of a legal design process.

This part of the Journal will showcase the best work and developments in legal design. This can be in the form of text, digital artifacts, reports, visualisations or any other media that we can distribute in a digital journal format. Text submissions can be between 1,000 and 5,000 words and are reviewed by our Studio editorial team.

What kind of practical use cases can I submit?

Your submission should consist the following:

- Challenge: Describe the problem you had to solve

- Approach: Describe the selected design process and phases you went through in order to solve the challenge. Please insert also a section of the impact that your concept will bring or brought.

- Solution: Show us the solution you developed. Not only with words but with images.

Make sure you do have permission and the rights to share your project an materials (such as images and use case stories etc.)

Why is there a review process?

How does the review process look like and how do we select use cases for publication ?

- Aesthetics

- Depth of concept (Why, What, How)

- Process steps you selected

- Impact

What are the requirements for submission?

Please find a list of requirements and tips here.

Do you want to share your Legal Design Story with the world?

Why publish with us?

Reputation

The editorial teams are comprised of many of the leading legal design academics and practitioners from around the world.

Diamond open access

We are a diamond open-access journal, digital and completely free to readers, authors and their institutions. We charge no processing fees for authors or institutions. The journal uses a Creative Commons BY 4.0 licence.

Rigour and quality

We are using double blind peer review for Articles and editorial review for the Studio. Articles are hosted on Scholastica which is optimised for search and integration with academic indices, Google Scholar etc.

Your Studio Editorial Collective

Do you want to see more use cases ? Take a look at the websites of some of our Studio editorial team.